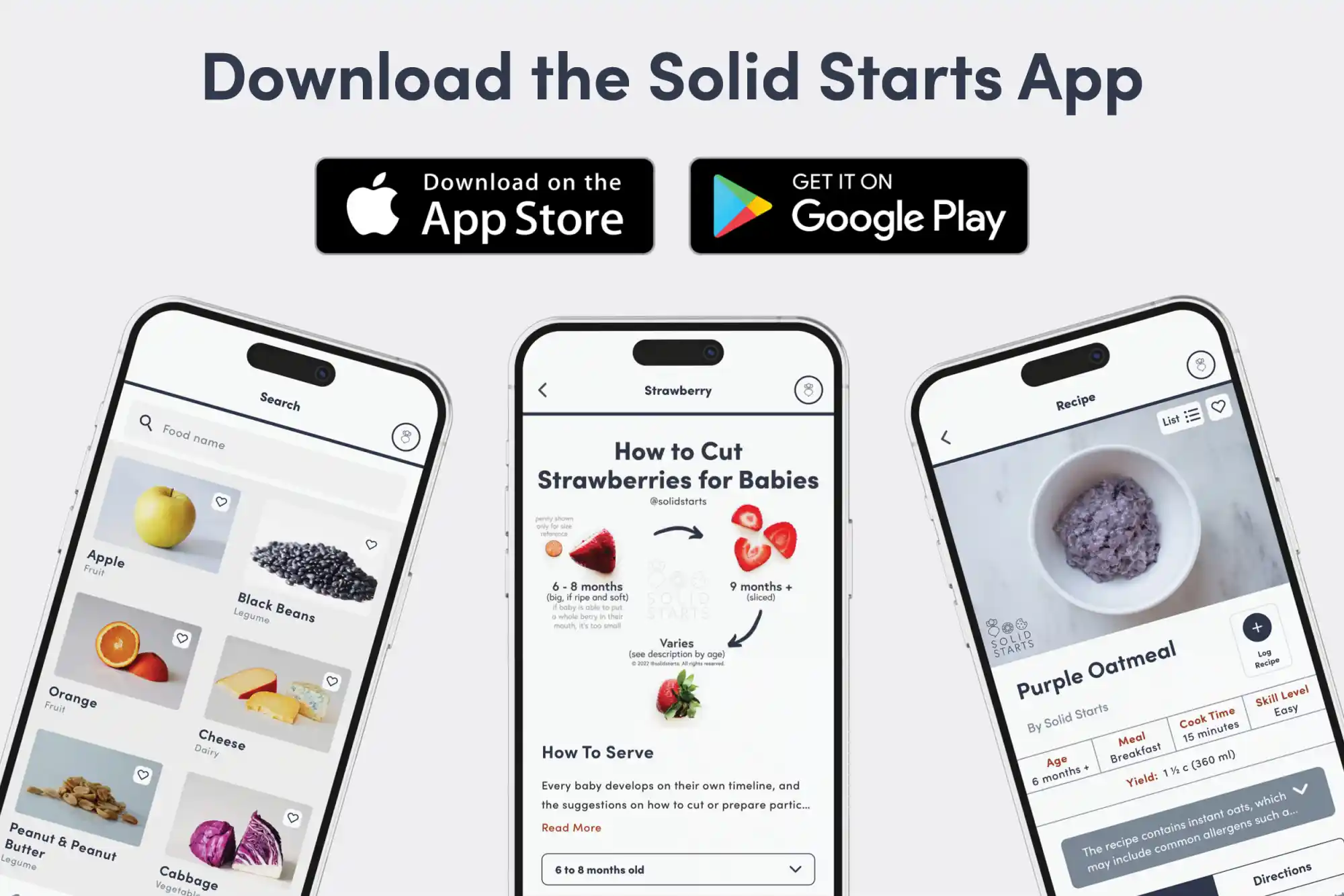

Access our First Foods® Database in the Solid Starts App.

Learn more

When can babies have cheese?

Cheese, as long as it is pasteurized to minimize the risk of foodborne illness, may be introduced as soon as baby is ready to start solids, which is generally around 6 months of age. While cheese can be high in sodium, an occasional taste is fine as part of a balanced diet.

Cheese can be made from any type of milk. This ancient food has its origins in the area around the Mediterranean Sea, where cheese was made with milk from domesticated cows, goats, and sheep in the 7th century B.C. Further east in Asia, cheese was traditionally made with milk from other animals, like water buffalo and yak. Flavor and texture varies depending on the source of the milk, the type of bacteria used to ferment the cheese, and the preparation method.

How do you serve cheese to babies?

Every baby develops on their own timeline, and the suggestions on how to cut or prepare particular foods are generalizations for a broad audience.

6 months old +:

Thinly spread pasteurized soft cheeses like cream cheese, labneh, or fresh ricotta cheese on toasted bread or other finger foods. Alternatively, offer some in a bowl for baby to scoop. At this age, you can also offer long, flat pieces of pasteurized semi-firm cheeses like cheddar or swiss cheese for baby to grab, hold, and munch. Shredded cheese can be melted into a variety of foods, but sprinkle sparingly, as large globs of melted cheese increase the risk of choking. While salty cheeses like feta or parmesan contain a lot of sodium, a taste here and there as part of a balanced diet is fine, too. Avoid cubes and large chunks of cheese due to increased choking risk, and do not offer unpasteurized cheese or cheeses that are mold- or smear-ripened, such as brie or camembert due to the risk of foodborne illness.

9 months old +:

When you see signs that baby is developing the pincer grasp (where the tips of the thumb and pointer finger meet), offer bite-sized pieces cut from a flat slice of pasteurized semi-firm cheese for baby to practice picking up or long, flat slices of cheese to take bites from. Shredded cheese can be served on its own or can be melted into a variety of foods, but when serving this way, sprinkle sparingly, as large globs of melted cheese increase the risk of choking. Alternatively, continue to serve pasteurized soft cheeses like labneh, mascarpone, or fresh ricotta cheese either in a bowl for baby to scoop or thinly spread on toasted bread or other finger foods. Continue to avoid cubes and large chunks of cheese due to increased choking risk, and do not offer unpasteurized cheese or cheeses that are mold- or smear-ripened, such as brie or camembert due to the risk of foodborne illness.

12 months old +:

Offer soft cheeses, melted or thinly sliced semi-firm cheeses, or melted, crumbled, or grated hard cheeses in a variety of ways: on bread, eggs, vegetables or folded into grain or bean dishes. At this age, you can offer melted cheese in a thin layer on top of foods (such as an open-faced sandwich or piece of toast or tortilla), but continue to remove large globs of melted cheese. Make sure the child is in a safe eating environment and never serve cheese on-the-go in a stroller, in a car seat, or when your toddler is running around. Continue to avoid cubes of cheese, as well as raw/unpasteurized cheeses.

How to prepare cheese for babies 6 months +

How to prepare cheese for older babies and toddlers

Videos

Is cheese a choking hazard for babies?

Yes. Cheese can be firm and springy, and it can form a sticky mass in the mouth—all qualities that increase choking risk. To reduce the risk, prepare and serve cheeses in an age-appropriate way. As always, make sure you create a safe eating environment and stay within an arm’s reach of baby during meals.

Learn the signs of choking and gagging and more about choking first aid in our free guides, Infant Rescue and Toddler Rescue.

Is cheese a common allergen?

Yes. Cheese is often made from cow’s milk, which is classified as a Global Priority Allergen by the World Health Organization. It is an especially common food allergen in young children, accounting for about one-fifth of all childhood food allergies. Keep in mind that dairy products from other ruminants such as buffalo, goat, and sheep may provoke similar allergic reactions to cow’s milk dairy products. That said, there’s good news: milk allergy often disappears with time. Research shows that the majority of children with cow's milk allergy will outgrow it by age 6, and many babies with milder symptoms of milk protein allergy (which can show up as painless blood in stool) are able to successfully reintroduce cow's milk as early as their first birthday, with the guidance of their appropriate pediatric health professionals. Note: Aged cheeses generally contain histamines, which may cause rashes in children who are sensitive to them.

Milk is a common cause of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, also known as FPIES. FPIES is a delayed allergy to food protein which causes the sudden onset of repetitive vomiting and diarrhea to begin a few hours after ingestion. This is termed acute FPIES. Left untreated, the reaction can result in significant dehydration. When milk is in the diet regularly, FPIES can present as reflux, weight loss, and failure to thrive - this is termed chronic FPIES. Symptoms generally improve with elimination of milk from the baby’s diet. Thankfully, like other forms of milk allergy, FPIES which presents early in life is generally outgrown by the time a child has reached 3 to 5 years of age.

Lactose intolerance, which is when the body has a hard time processing lactose, the sugar that is naturally present in milk, can sometimes be mistaken for an allergy, as it can result in bloating, gas, diarrhea, nausea, and other discomfort. For those with older children who are lactose intolerant (keep in mind this is uncommon for infants and toddlers), some good news: compared with milk and certain other dairy products, many cheeses may be better tolerated by those with lactose intolerance, particularly aged cheeses, which have lower lactose content. Be sure to connect with an appropriate pediatric health care professional for any questions about lactose intolerance, and know there are many lactose-free dairy foods available.

If you suspect baby may be allergic to milk, consult an allergist before introducing dairy products like cheese. Based on a baby’s risk factors and history, your allergist may recommend allergy testing, or may instead advise dairy introduction under medical supervision in the office. If the risk is low, you may be advised to go ahead and introduce cheese in the home setting.

As with all common allergens, start by serving a small quantity on its own for the first few servings, and if there is no adverse reaction, gradually increase the quantity over future meals. If you have already introduced milk and ruled out an allergy, cheese can be introduced as desired, without any need to start small and build up over time.

Is cheese healthy for babies?

Yes. Most cheeses are rich in protein, fat, calcium, selenium, zinc, and vitamins A and B12. Together, these nutrients work together to provide the building blocks for growth, development, and brain function. They also help support bone density, taste perception, vision, energy, and immunity. When shopping, choose pasteurized cheese to minimize the risk of foodborne illness.

Cheese contains some sodium, which supports hydration, movement, and the balance of electrolytes in the body. Consider serving high-sodium cheeses like feta or parmesan only occasionally, as baby’s sodium needs are generally low. That said, the amount of solid food that baby consumes tends to be low as they practice feeding themselves, and as a result, the amount of sodium consumed also tends to be low. Learn more about sodium in food for babies.

How much cheese can babies eat?

There is not a limit; if desired, you could serve pasteurized cheeses every day, but try not to worry about the exact amounts baby is consuming. During any given meal, a baby may eat lots of the cheese, or they may eat very little. Both scenarios are fine when cheese is part of a variety of foods in the diet.

When can children have unpasteurized (raw) cheese?

There is no age at which eating raw cheese is without risk, so whether or when to serve it is a personal decision for which you must make an informed decision in the context of your child. Unpasteurized or raw cheese poses a high risk of foodborne illness, especially salmonellosis and listeriosis, which are harmful bacterial infections for babies, children, and adults alike, with more risk of severe symptoms in babies.

Can babies have vegan cheese?

Yes, as long as it is prepared in an age-appropriate way to reduce the risk of choking, and any common allergens in the cheese, such as soy, tree nuts, or wheat, have been safely introduced. There are nut-, oil-, pea- and/or soy-based vegan cheeses, so know there are lots of options to choose from, depending on what your family’s needs are.

Our Team

Written by

Get 10% Off

Sign up to save and get weekly tips, recipes and more.

Copyright © 2026 • Solid Starts Inc