Tongue Thrust and Starting Solids

You may have heard that one of the signs of readiness for solid food is the disappearance of the tongue thrust. This claim, however, is not supported by research and it is our professional opinion that the thrust can be helpful when starting solids.

What is tongue thrust?

The tongue thrust, or extrusion reflex, is a reflex present at birth that persists until 4 to 7 months of age in typically developing babies. In young infants, the tongue thrust is stimulated by touching the tip of the tongue, causing the tongue to “thrust” or stick out of the mouth. A strong tongue thrust reflex causes the tongue to extend past the gums and lips; a tongue tie may cause some restriction.

Another reflex present at birth is the root reflex. This reflex helps baby latch at the breast or on a bottle nipple and causes baby’s tongue to extend or stick out of the mouth before it pulls the breast or bottle into the mouth. Like the tongue thrust reflex, the root reflex is present until 4 to 6 months of age.

Because of the tongue thrust and root reflexes, the forward thrusting of the tongue is a well-established and strong movement pattern by 6 months of age, even if the reflexes have integrated or disappeared.

Charlie, one month old.

Charlie, one month old.

What does the tongue thrust reflex do?

Interestingly, the evidence in this area is lacking; there is almost no research examining the function of the tongue thrust. Most documentation is clinical opinion based on observations of dentists, lactation consultants, feeding therapists, and pediatricians.

Many experts believe the primary functions of the tongue thrust reflex include:

Swiftly pushing items out of the mouth

Keeping the airway clear

Protecting against choking

Newborns and young infants have immature oral motor skills, poor head and neck control, and often lie on their backs or in a reclined position with gravity moving things towards their throat. Additionally, babies lack the fine motor skills needed to pull items out of the mouth. So, without the tongue thrust, if any item should accidentally end up in the mouth, an infant would be at a high risk of choking. The tongue thrust reflex appears to protect infants with reflexive skills enabling them to push things back out of the mouth when necessary. As the reflex fades and babies learn more coordinated tongue and finger movements, they can spit things out of their mouth as needed.

Some professionals feel the tongue thrust reflex is present to help babies stick out their tongue to latch at the breast, but we disagree with this theory. To latch, the baby’s head needs to turn towards the breast or bottle, the mouth needs to open wide, the tongue needs to drop in the mouth and gently extend over the lower gum ridge, and then it needs to cup or make a “U” shape around the nipple. This constellation of movements is the root reflex. Comparatively, the tongue thrust reflex lacks the additional elements needed to latch. In fact, the tongue thrust can immediately push an item back out of the baby’s mouth after a latch is established, which can be problematic for breast or bottle feeding.

Riley, 6 months, thrusts a too-big bite of banana out of her mouth.

Why do some recommend waiting to start solids until the tongue thrust reflex disappears?

In the context of spoon-feeding, it’s functional to wait for the tongue thrust reflex to fade because it’s difficult for baby to move puree back to swallow otherwise. Logically, this reflex would be a nuisance while spoon-feeding pureed food into a baby’s mouth. As the spoon touches the tongue tip, the tongue protrudes out, pushing all the puree out of the mouth. Baby doesn’t have a chance to learn how to move the food back to swallow because it all ends up on their chin. Some spoon-fed babies learn to push the tongue on the spoon and suck the puree off, which is the same pattern used with a bottle.

Additionally, there is a misconception that a baby is not ready to swallow food until the thrust disappears, but that recommendation is not rooted in evidence. Swallowing is a deep brainstem reflex, which is how babies know to swallow purees after using the same bottle-sucking pattern described above. Babies do not have to learn how to swallow.

As with many suggestions in infant feeding, there is no clear rationale for the recommendation to wait for solids until the tongue thrust disappears.

Why should we not wait for the tongue thrust reflex to disappear before starting solids?

Purees don’t advance a baby’s chewing skills in a meaningful way. In fact, there is a critical window between 6 to 9 months of age where you must take a leap and give baby something chewable to eat so they learn to chew. Babies who only eat purees during this critical window are at heightened risk for poor chewing and picky eating as children.

Until the day baby tries solid foods, baby has used a single oral motor pattern to eat: a sucking pattern. In the weeks leading up to starting solids, baby develops important gross and fine motor skills to support learning to eat; however, there is little to no shift in baby’s oral motor patterns to make them suddenly more coordinated with chewing.

Babies need chewable foods to learn how to chew and the tongue thrust reflex offers some level of protection while baby is developing the skills to move food safely around the mouth.

Oral-motor skill development when starting solids with finger foods

When starting finger foods, baby learns a new set of movement patterns and gains efficiency and coordination to chew and swallow solids safely. As the tongue thrust reflex integrates (usually between 4 to 7 months), babies don’t automatically know other oral motor patterns. They still need to break the dominant motor pattern of moving the tongue exclusively forward, backward, and sucking.

There are three dominant reflexes in play when baby starts solids:

Tongue thrust reflex

Tongue lateralization reflex

Gag reflex

These reflexes help babies learn new movement patterns necessary to eat while staying safe. All babies have to learn these new patterns, whether starting with finger foods at 6 months or starting with purees and moving to finger foods later. These reflexes also help the brain build a “mental map” of the mouth, allowing babies to gain more control, and figure out how to move, chew, and swallow food appropriately and confidently.

Tongue thrust

While a strong tongue thrust reflex often prevents a spoonful of purees from entering the mouth, it helps self-feeding babies learn about food. When a baby holds food while touching the lips and front of the tongue, the tongue automatically sticks out and explores the food by licking it. When babies put food in their mouth, they often override the tongue thrust by controlling the action of putting food in their mouth and by placing longer/bigger pieces of food towards the side of the mouth, triggering the tongue lateralization reflex.

Importantly, a lingering tongue thrust can also be helpful in pushing too-big pieces of food in the mouth forward and out, an additional protective layer to guard against choking.

Tongue lateralization reflex

Babies are born with the tongue lateralization reflex, which is present until about 9 months of age. When you touch the side of the baby’s tongue, it darts to that side. This reflex causes the tongue to move sideways towards the stimulus in the mouth to touch, lick, and explore whatever touches the tongue.

Maeve, 4 months, teethes on an infant toothbrush.

Notice when you chew food: your tongue moves sideways to push food toward your molars for chewing. That’s tongue lateralization but, for you, it’s not a reflex anymore—it’s an established motor pattern your brain uses to move and chew food.

Self-feeding stick-shaped pieces of food engages tongue lateralization and helps baby learn the building blocks of moving food in the mouth. The more the tongue learns to move side to side, the more the forward/backward pattern (tongue thrust) diminishes.

Gag reflex

Another layer of protection is the gag reflex, which also helps keep food towards the front of the mouth. Together, the tongue thrust and gag help push any poorly chewed food back out of the mouth.

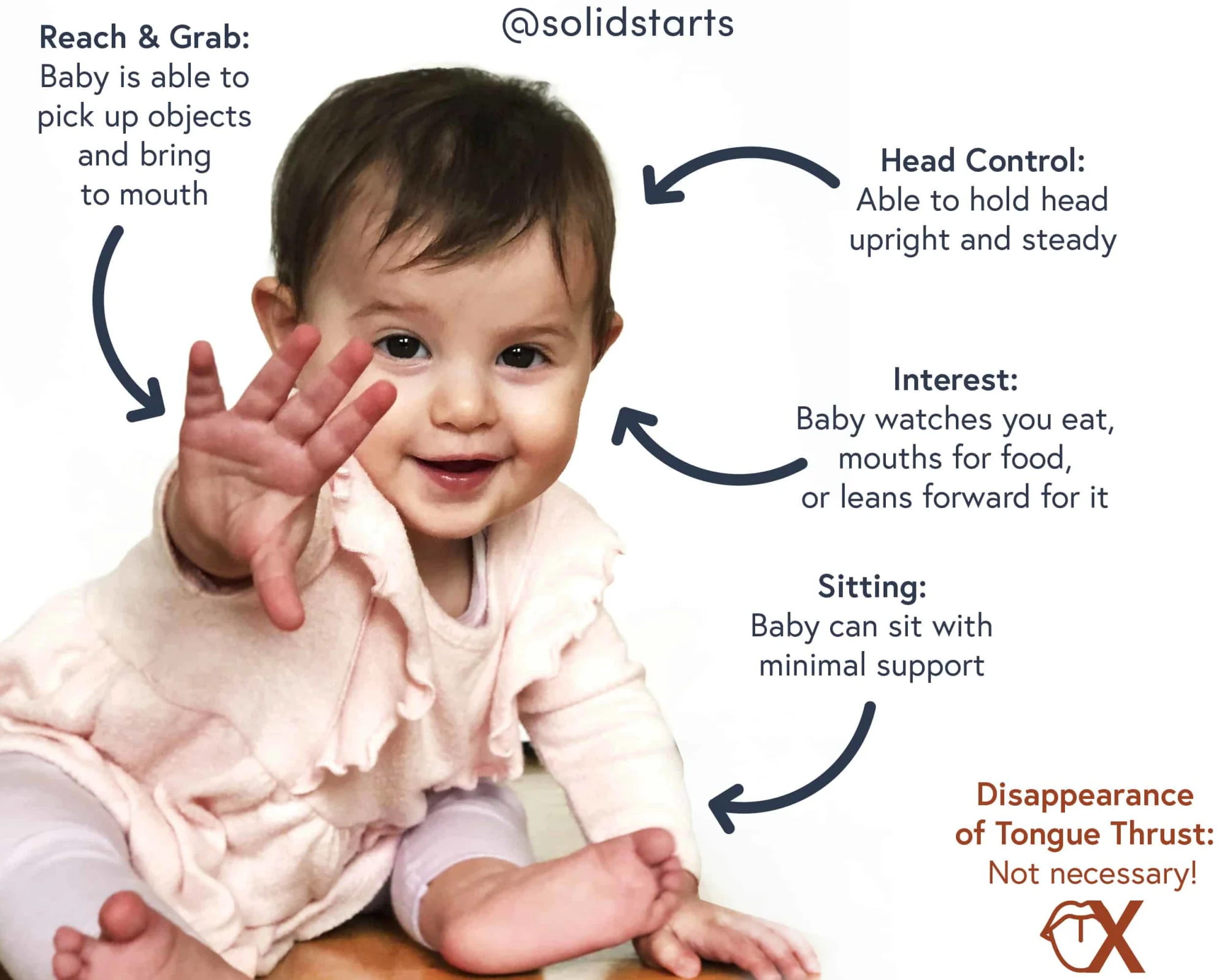

Must babies lose their tongue thrust reflex before starting solids?

No. In fact, there are distinct benefits to starting finger foods when baby still has the tongue thrust reflex.

Be mindful that if you plan to start by spoon-feeding purees, most of the food will end up on baby’s chin with a tongue thrust reflex in place. This doesn’t mean baby doesn’t like it; it just means they don’t have the skill to move past the tongue thrust just yet.

Additionally, if you offer exclusive purees for more than a few weeks, it’s likely the tongue thrust reflex will diminish before offering finger foods. This simply means that baby will likely rely on the gag reflex as the primary way to move food forward and out of the mouth while learning to chew rather than the tongue thrust to push food out quickly.

To recap:

The tongue thrust reflex is beneficial for oral motor development and learning to eat finger foods.

The tongue thrust offers multiple layers of protection to a young baby:

Pushes food (and objects) out of the mouth

Keeps the airway clear

Protects against choking

Exploring solid foods with the mouth is critical to build a mental map of the mouth. As things touch the inside of the mouth, the brain slowly “draws” a map.

The tongue thrust and gag reflexes keep food forward in the mouth, protecting the throat from unchewed food that isn’t ready to swallow.

When babies start solids with a tongue thrust reflex in place, they learn how to override the dominant tongue thrust pattern and move the tongue in new directions using the tongue lateralization reflex.

Self-feeding stick-shaped pieces of food engages tongue lateralization and helps baby learn the building blocks of moving food in the mouth.

As pediatric feeding specialists with extensive training in oral motor skill development, clinical experience working directly with thousands of infants to develop oral motor skills to eat solids and observing typically developing babies as they learn to eat, we want to share our understanding and the importance of the tongue thrust reflex for helping a baby learn to chew. We acknowledge that our conclusions are based on clinical experience and observation, but we included literature when available.

Kary Rappaport, OTR/L, MS, SCFES, IBCLC

Kimberly Grenawitzke, OTD, OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC, CNT

Ready to get started?

Download the app to start your journey.

Expert Tips Delivered to Your Inbox

Sign up for weekly tips, recipes and more!

Copyright © 2026 • Solid Starts Inc