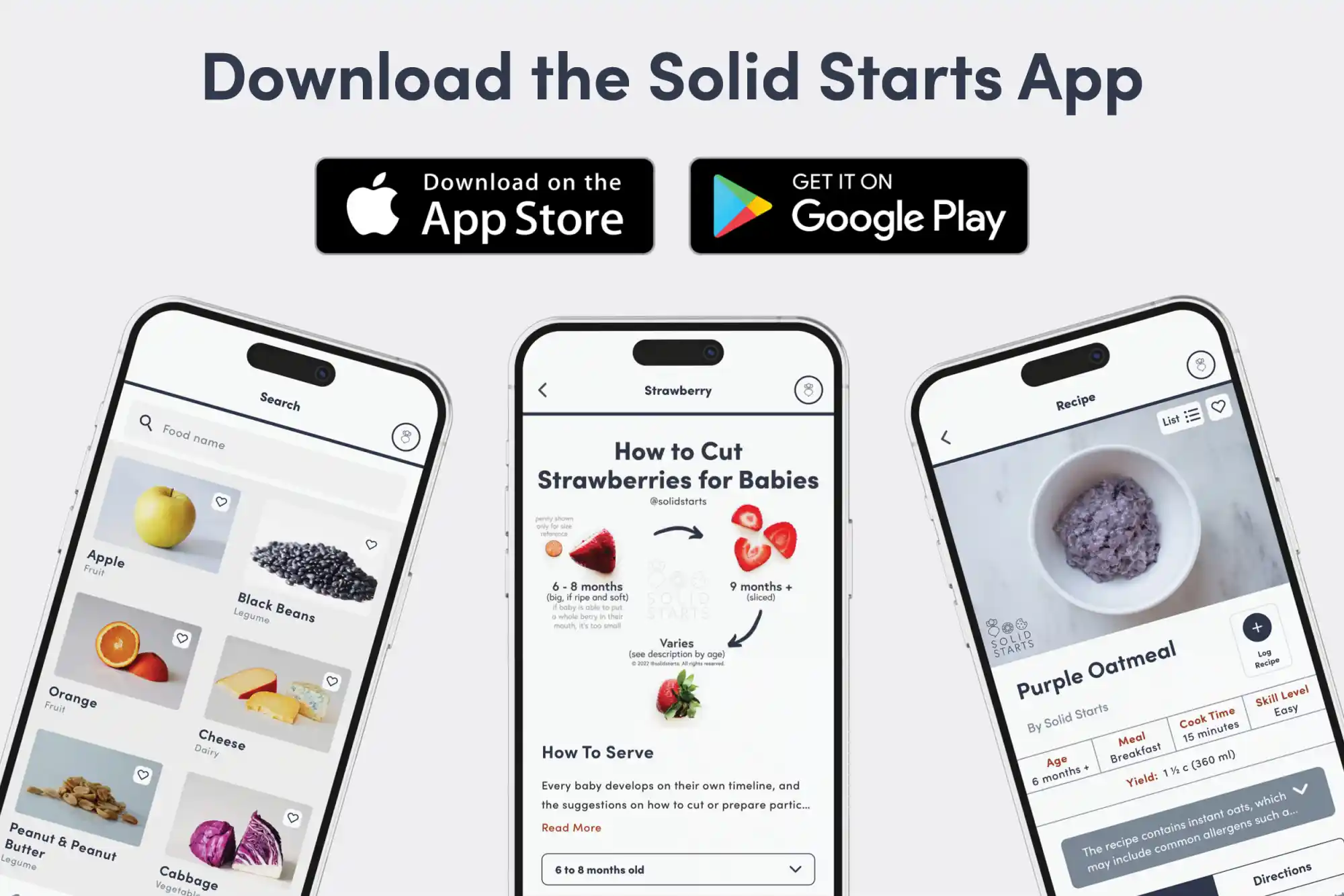

Access our First Foods® Database in the Solid Starts App.

Learn moreCarrot

Vegetable

Age Suggestion

6 months

Iron-Rich

No

Common Allergen

No

Warning

Raw carrot is a common choking hazard, especially in the form of baby carrots and carrot sticks. Keep reading to learn more about safely introducing carrot to babies.

When can babies have carrots?

Carrots may be introduced as soon as a baby is ready to start solids, which is generally around 6 months of age.

Carrots are often orange and sweet, but they weren’t always that way. The root vegetable originated in Southwest Asia, where humans initially harvested the carrot’s aromatic foliage and seeds as food and medicine. Eventually, people learned to eat the plant’s root as well, which was not orange, but yellow or purple, spindly in shape, and more bitter than the modern carrot.

How do you serve carrots to babies?

Every baby develops on their own timeline, and the suggestions on how to cut or prepare particular foods are generalizations for a broad audience.

6 months old +:

Cook whole peeled carrot (bigger is better) until it is completely soft and easily pierced with a knife, then cut the vegetable in half lengthwise and hand it over in the air. Alternatively, mash the cooked carrot and offer in a bowl for baby to scoop or on a pre-loaded spoon.

You may, at your own risk, also offer a thick raw carrot stick (aim for around 1 inch or 2 cm in diameter at both ends of the carrot stick, avoiding the tapered end that could more easily snap off), peeled for baby to gnaw, an activity that won’t lead to any food in the belly at that meal, but has immeasurable benefits for strengthening the jaw, helping the tongue learn to move food to the side of the mouth where the molars will eventually grow in, and providing sensory feedback for baby to “map” the inside of the mouth. These actions help support the development of chewing coordination. While unlikely, for babies with teeth and a strong jaw, it is possible to bite off a piece of carrot. If this happens, give baby a moment to spit it out, keeping your fingers out of baby’s mouth. You can help by putting your hand on baby’s back and gently leaning the baby forward to allow gravity to help pull the piece of food towards the front of the mouth for baby to more easily spit out. Those moments can feel scary, but they are valuable teaching moments for baby to learn what isn’t safe to swallow and to practice spitting out foods.

9 months old +:

At this age, babies develop a pincer grasp (where the thumb and forefinger meet), which enables them to pick up smaller pieces of food. When you see signs of this development happening, try moving down in size by offering cooked carrots cut into bite-sized pieces. You can also offer grated raw carrot.

18 months old +:

Continue to offer whole carrots that have been cooked and cut into bite-sized pieces, or if you like, larger pieces as a finger food. Many toddlers are ready to handle raw carrots closer to age two. If you feel comfortable with the child’s eating skills, you can offer raw carrot that has been cut into sticks by quartering raw carrots lengthwise. As always, you can reduce the risk of choking by making sure to create a safe eating environment and stay within arm’s reach at mealtime.

24 months old +:

Continue to offer cooked carrots as desired and raw carrots cut into sticks. If you have not yet offered raw carrots cut into sticks, you may want to begin there before progressing to whole baby carrots. When a child is regularly showing mature chewing skills (taking small bites, moving food to the side of the mouth to be chewed and chewing thoroughly, and not stuffing too much food in their mouth), they may be ready to practice eating whole, raw, baby carrots in a safe, supervised setting. Raw baby carrots pose a high choking risk because of their shape and firm texture, so offer them when a child is seated, engaged in eating, and when you can supervise mealtime closely.

We suggest demonstrating chewing with the molars prior to offering the whole, raw, baby carrot: open your mouth, place the vegetable on your back teeth and explain, “I am using my strong back teeth to crush this carrot, and I have to chew it A LOT.” You may want to consider holding the baby carrot for the child to practice biting—hold at the corner of their mouth and allow the child to close their teeth on the food. Coach the child to push hard to break through the baby carrot. You can make a big deal about the loud crunch sounds that happens when they chew through it.

If the toddler does not attempt to bite and chew with coaching, you can continue to serve thin, raw carrot sticks to help build chewing skill.

How to serve cooked carrots to babies 6 months +

How to offer raw carrot as a food teether to babies 6-8 months old

Videos

Are carrots a choking hazard for babies?

Yes. Carrots are a common choking hazard, particularly baby carrots and carrot sticks. To minimize the risk, cook carrot until soft and cut into age-appropriate sizes. As always, make sure to create a safe eating environment and stay within arm’s reach of baby at mealtime. For more information on choking, visit our sections on gagging and choking and familiarize yourself with the list of common choking hazards.

Are carrots a common allergen?

No. Allergies to carrot are rare, but they have been reported. People who are allergic to birch pollen may be allergic to raw carrots or experience Oral Allergy Syndrome (also known as pollen-food allergy). Oral Allergy Syndrome typically results in short-lived itching, tingling, or burning in the mouth and is unlikely to result in a dangerous reaction. Cooking the carrot can minimize the reaction.

As you would do when introducing any new food, start by serving a small amount on its own for the first couple of times. If there is no adverse reaction, gradually increase the amount served over future servings.

Are carrots healthy for babies?

Yes. Carrots of all colors offer carbohydrates, fluid, fiber, folate, magnesium, potassium, as well as vitamins A, B6, and K. Together, these nutrients support baby’s energy for play and exploration, hydration, digestive health, brain development, electrolyte balance, vision, and more. Carrots also offer antioxidants and carotenoids like lutein and zeaxanthin that support bodily repair and vision.

When can babies and toddlers have raw baby carrots?

It depends but it is generally safest to wait until closer to age two. Raw baby carrots pose a high choking risk because of their shape and firm texture. Like regular carrots, cooking baby carrots until soft minimizes the risk for babies and young toddlers. To minimize the risk further, slice lengthwise in halves or quarters. Never offer whole raw baby carrots to a baby and only offer raw baby carrots to toddlers when you are confident in the toddler’s chewing abilities, likely around age two, or when the child has had practice breaking down food with their molars.

Do I need to worry about the nitrates in carrots?

No. Feel free to offer vegetables that contain nitrates (arugula, beets, carrots, lettuce, spinach, and squash to name a few) as part of a variety of foods in the diet. Nitrates are naturally-occurring compounds which, if consumed in excess, may negatively affect oxygen levels in the blood. That said, babies who are allowed to self-feed typically do not consume excessive amounts of solid food because they need lots of practice to learn how to eat it. Nitrates in vegetables are generally not a cause for concern, and the benefits of introducing vegetables with nitrates as part of a balanced diet typically outweigh the unlikely risk of excessive consumption.

To reduce nitrate exposure, avoid consumption of untested well water and take care with purees. When possible, avoid homemade purees made with higher nitrate vegetables that are stored for more than 24 hours and commercial purees not consumed within 24 hours of opening. Higher nitrate vegetables include arugula, beets, carrots, lettuce, spinach, and squash, among others.

Our Team

Written by

Expert Tips Delivered to Your Inbox

Sign up for weekly tips, recipes and more!

Copyright © 2026 • Solid Starts Inc