6 Ways to Help Baby Practice the Pincer Grasp

Getting baby ready for smaller pieces of food

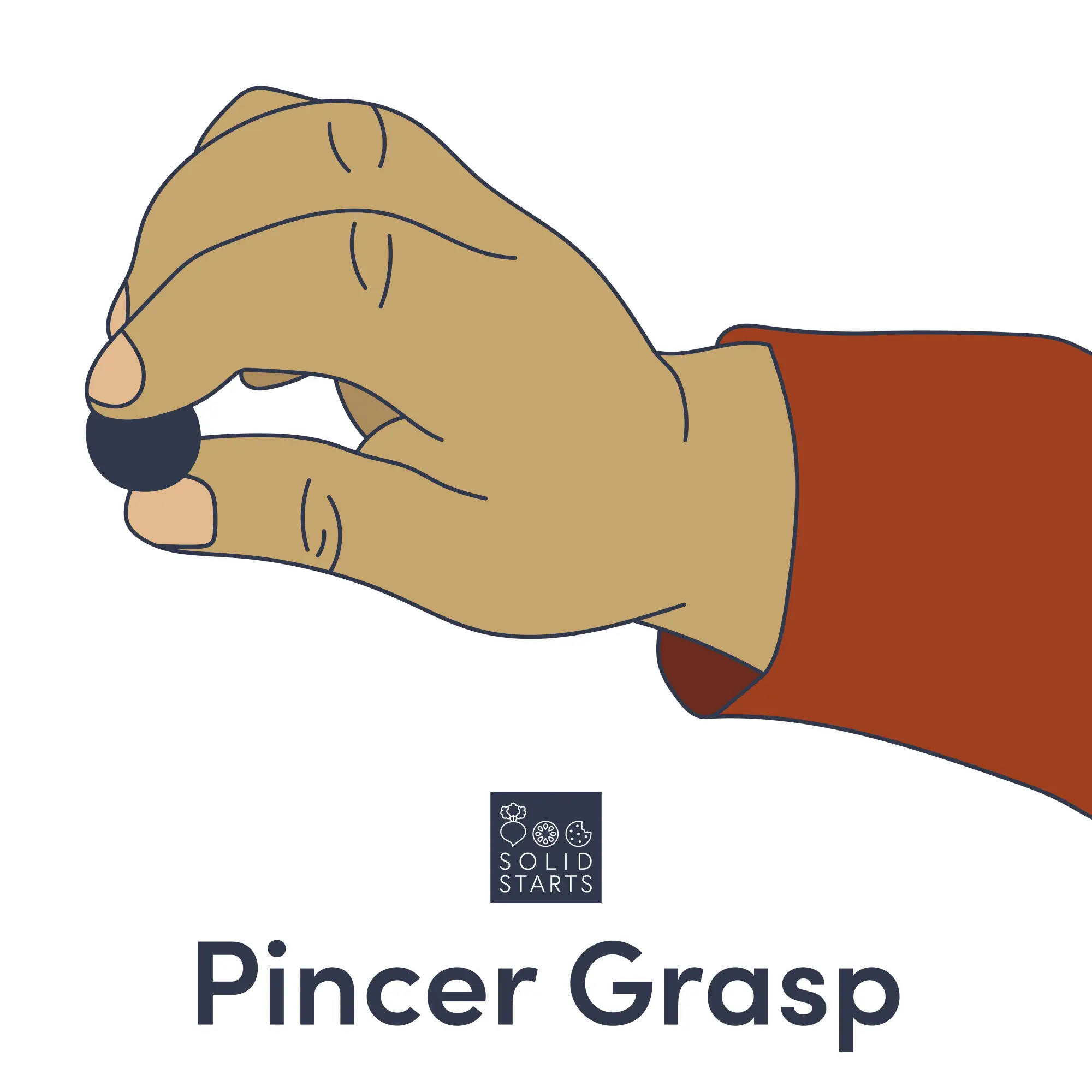

When babies start using their fingers to form a “pincer grasp” to pick up and move small objects, we’re often told that’s one sign they are ready to eat smaller pieces of food. But what, exactly, is a pincer grasp, how does it develop, why is it important, and how can we help baby learn to use it?

A pincer grasp simply means the tips of the thumb and index finger come together, a motion we use to pick up small items, pull zippers, and button shirts. Before babies develop a pincer grasp, they will use their whole hand—their fingers and palm together—to pick up, hold, and bring food into their mouths. Once a baby develops a pincer grasp, however, they are able to pick up smaller, individual pieces of food. As baby begins using a pincer grasp to self-feed, independently bringing food items to their mouths, they will continue to refine their chewing skills to manage smaller pieces.

Reflex leads to pincer grasp

For infants, each new ability builds on more basic skills. Sitting up and self-feeding, for example, become possible for baby only after months of practice learning how to roll over and grab at objects.

The pincer grasp is no exception: it evolves from a simple reflex. Press a finger into a newborn’s hand and watch them wrap their tiny fingers around it. This seems heartwarming and adorable, but it’s really just a response to pressure on baby’s palm, known as the palmar reflex. Reflexes are built-in movement patterns that help newborns build strength, find food, and learn about the world around them.

Over time, reflexes fade as babies learn to make more movements on purpose. At around 3 months, babies will start kicking their legs and reaching for items while lying on their backs; this builds their core muscles. At around 4 months, a baby will begin rolling and reaching for objects while on their tummy, strengthening their back muscles. Core and back strength lead to postural stability, which eventually allows a baby to sit upright, and later, to walk. These are known as gross motor skills.

Learning to use smaller muscles

This core strength and stability allows babies to focus on practicing fine motor movements, like the pincer grasp, which involve coordinating lots of small muscles in the arms, hands, and fingers.

At around 8 months, most babies will progress from a whole-hand grasp to an immature pincer grasp—the pads of their fingers meet, but not the tips. Some babies exhibit this skill at closer to 7 months of age. By 9 months, most babies refine this skill, with the tips of their thumb and forefinger meeting, and can effectively use a pincer grasp to pick up smaller food items such as a pea, a slice of grape, or a piece of cereal.

Maeve, 7 months, tries to pick up a small piece of pear, but isn't very successful.

William, 8 months, practices his emerging pincer grasp with small pieces of beef brisket.

Mouth skills may not match

Many caregivers wonder when it’s safe to start serving baby smaller pieces of food. Once babies can successfully use a pincer grasp to get bite-size foods into their mouth, they are ready to practice chewing and swallowing them. While research shows an increased risk of choking when someone else puts solid food into baby’s mouth, self-feeding actually reduces such risks, according to studies on the topic.

Even infants who are self-feeding with a mature pincer grasp may struggle with efficiently managing, chewing, and swallowing small or bite-size bits. That’s because a baby’s oral motor skills, like chewing, don’t necessarily develop at the same pace. Expect to see more spitting than swallowing as babies practice their eating skills. It’s also common to see food falling out of baby’s mouth, and lots of gagging. Need help with spitting? Check out this article. Learn more about gagging here.

William, 9 months, easily picks up a piece of strawberry using his pincer grasp, but spits the food out....

To hone baby’s skills, it’s essential to expose them to a variety of foods, bite sizes, shapes, and textures. Exposure and practice helps babies build new motor patterns, enabling them to safely eat all kinds of food

Even after a pincer grasp is present, however, it’s important to continue avoiding foods that are small, round, firm and slippery. These include whole seeds or nuts, little whole grapes, grapes halved at the center, or firm blueberries—foods that start out small and round rather than becoming smaller as a baby or toddler chews them. For babies who are learning to eat solids, even those with a well-developed pincer grasp, these food items present the greatest choking risk.

6 ways to help baby build their pincer grasp

Most babies develop and practice this skill by building on other movements. According to our occupational therapists, here are six ways you can help:

1. Provide plenty of floor time to encourage large movements, like rolling and crawling

Back and tummy time on the floor builds core muscles. This helps babies feel stable enough to reach out and start using their fingers to grab objects. Make floor time as fun as possible to steadily build baby’s endurance by placing toys and high-contrast cards just out of reach, encouraging them to roll over and try to grab them. Crawling is especially good for building hand and shoulder muscles. Crawling helps develop hand-eye coordination, a building block for later skills like catching a ball or handwriting.

2. Create opportunities to pull and squeeze

We haven’t yet met a baby who doesn’t like pulling all the wipes out of the wipe container. A reusable homemade tissue-pull box—basically, an empty tissue box stuffed with colorful fabric squares or recycled gift tissue—allows baby to practice their grasping skills without making a huge mess. *Always supervise to be sure recycled gift tissue does not end up in baby’s mouth.

Riley, 8 months, pulls fabric tissues from a box....

3. Let baby play with small, safe foods

Between 6 and 9 months, most babies become more coordinated about picking up items. Because most babies will put those objects in their mouths, why not let them practice with food? As baby gets better at picking up larger, stick-shaped foods, gradually begin offering smaller pieces. Especially between 8 and 9 months, try giving baby soft-cooked beans, slightly smashed soft peas, or “O” cereals. If they can independently get these bite-sized pieces to their mouth, they are ready to practice the oral skills needed to manage them.

4. Practice pointing together

Pointing is a great way to help babies learn to use individual fingers. Most babies don’t start pointing on their own until around 9 months. Encourage pointing (and build language skills) by reading books to babies and pointing at the pictures you’re reading about.

5. Play with tube-shaped toys

When babies are first developing the ability to use their hands to grasp and explore, they may practice with larger items that they can grab at with their whole hand. Knobby balls, stacking cups, or rattles a little bigger than a baby’s hand are some of the easiest toys for young infants to pick up. Cylindrical items are particularly useful because, in order to pick them up, a baby’s hand must form the rounded “O” shape they will need for the pincer grasp. These can include the cardboard inside of a paper towel roll, a ring stacker, and puzzle pieces with dowels. As baby gets closer to 9 months, try offering smaller cylindrical items such as tubular pasta or a flexible silicone straw.

Amelia, 9 months, pulls straws out of a cup....

6. Serve food on the tray, not in a bowl or plate

Small bowls and plates help to keep pieces of food contained, making it easier for babies to use their whole hands to scoop. Serving bite-sized food pieces scattered on the tray encourages baby to try picking up an individual piece of food with thumb and forefinger rather than scooping. Even if baby only ends up pushing the food around the tray with their finger, the activity offers valuable practice.

In the end, any opportunities for babies use their core muscles, hands, and fingers will help them build strength, coordination, and dexterity. All of which helps babies perfect their pincer grasp and go on to master other important eating skills.

Providing support, solving problems, and seeking help

For babies, lifting small bits of food with a pincer grasp takes intense focus and many muscles working together.

If a baby is using lots of energy just to sit up and remain stable, studies show they will go back to using easier but less efficient whole-hand grasps.

If baby is close to a year and frequently reverts to a whole-hand grasp, be sure to let their doctor know, as baby may need help building more trunk and arm strength.

If baby is 12 months or older and not yet attempting a pincer grasp, tell their healthcare provider so they can determine if baby needs help building fine motor skills.

As the pincer grasp develops and becomes easier, it’s common for some babies to overstuff their mouths with small bits of food. Overstuffing usually is a passing phase, but it can slightly increase baby’s risk of choking. Check out our page on pocketing, shoving, and overstuffing to learn more.

Reviewed by:

K. Grenawitzke, OTD, OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC, CNT

K. Rappaport, OTR/L, MS, SCFES, IBCLC

D. Roberts, MS, OTR/L, IBCLC

Ready to get started?

Download the app to start your journey.

Expert Tips Delivered to Your Inbox

Sign up for weekly tips, recipes and more!

Copyright © 2026 • Solid Starts Inc