Gagging vs. Choking

It is normal for babies to gag when starting solids, and typically, gagging is not a cause for concern. Choking, however, is an emergency that requires immediate medical care. Our pediatric pros explain the difference—and how to safely respond.

At A Glance

Gagging is expected when starting solids. Babies gag as they explore different shapes and textures, which helps them learn how to manage food in the mouth.

Before starting solids, review the difference between gagging and choking. This can help put your mind at ease when gagging happens.

When baby gags, remember: gagging helps prevent choking. Gagging does not lead to choking. Gagging is a reflex that protects baby by expelling food away from the throat.

To minimize gagging, consider food texture: soft foods and loose grains tend to cause more gagging, while food teethers help minimize gagging.

While baby’s body is built to protect itself, choking can happen. Take steps to lower the risk of choking.

One way to help prevent choking: do not put food in baby’s mouth. Instead, let baby practice feeding themselves, which has many developmental benefits.

What is gagging?

Gagging happens instinctively when food is in the mouth and the brain doesn’t think it should be there. It can also happen when the tongue loses control of food. Gagging is the brain’s way of saying, “Something isn’t right here. I don’t want to choke on it.”

Gagging is protective reflex that helps prevent choking. When the gag reflex kicks in, the throat contracts to help push food forward and stops the body from swallowing it. At the same time, the breathing tube closes briefly to prevent anything from going into it.

Gagging is part of learning how to eat real food. All babies gag as they start solids, whether they begin with purees or finger food. With consistent opportunities to practice eating a variety of textures, babies gag less over time.

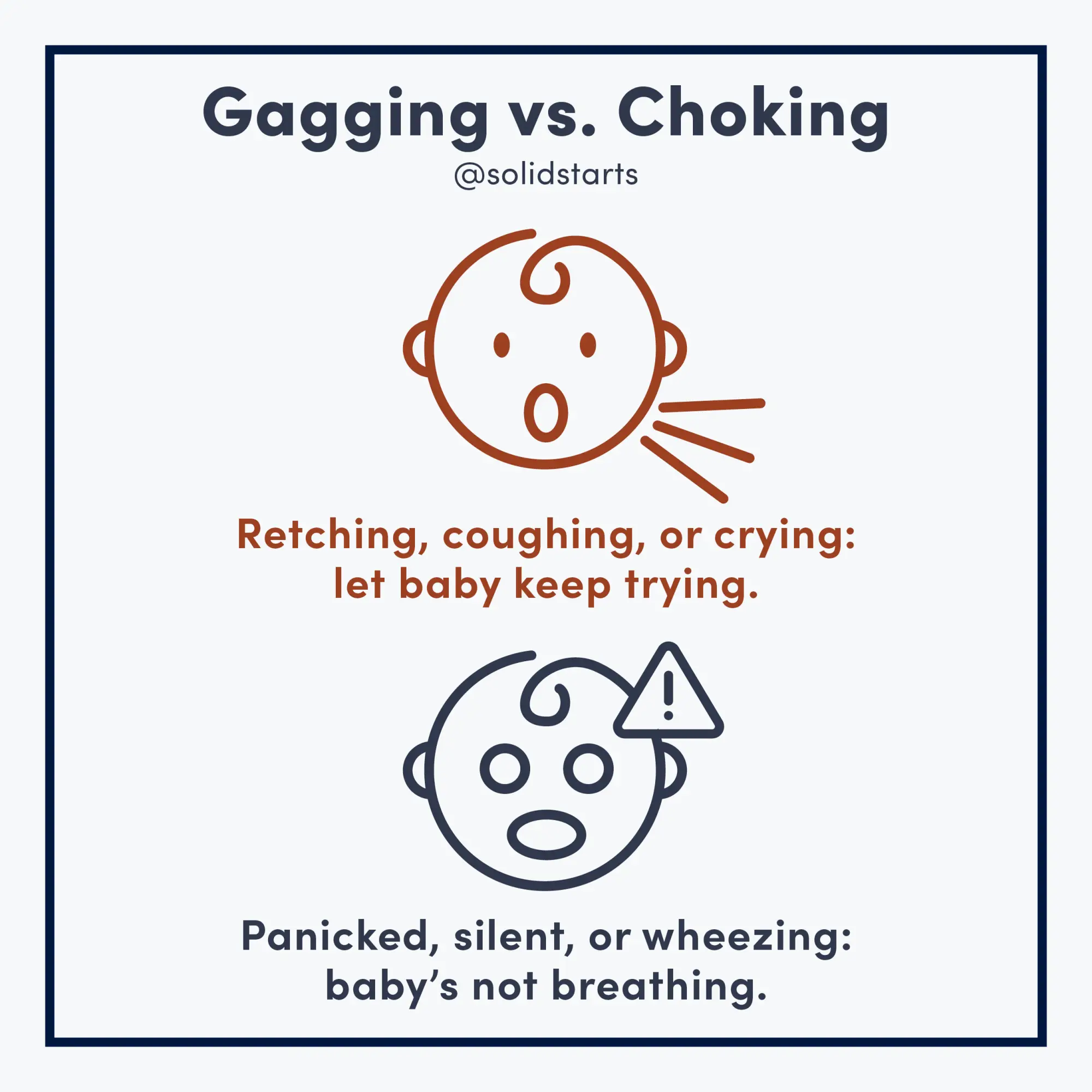

What is the difference between choking and gagging?

Choking happens when the airway is blocked, and the body has trouble breathing. Gagging is often misinterpreted as choking. It’s not uncommon to hear an adult say, “Baby was choking!” when actually, baby was coughing or retching and still able to breathe.

Signs of baby choking can include:

inability to cry or cough

difficulty breathing

skin tugging into the chest

look of terror

high-pitched sounds

skin color changes, typically around the mouth (ranging from blue to purple to ashen-like)

Signs of baby gagging look a little different:

retching, and sometimes vomiting

coughing

crying

open mouth

cupped tongue

red or purple color of the face

Choking is generally silent because the airway is blocked. Choking is a life-threatening emergency that requires immediate intervention.

If you suspect baby is choking, use a speaker phone to call 9-1-1 or local emergency services. This way, your hands are free to perform infant rescue. If another adult is present, one of you should immediately perform infant rescue while the other calls for help.

Kary Rappaport, Pediatric Feeding/Swallowing Specialist, explains the difference between gagging and choking.

What to do if baby gags?

Gagging is not an emergency. When we gag, we hold our breath, and the airway briefly closes. This prevents vomit from entering the breathing tube when gagging causes the body to throw up. Sometimes gagging looks like breathlessness, but observe closely: you’ll notice baby takes a breath in-between gags or after gagging.

Do not stick your finger in baby’s mouth when they are gagging. This can push food further into the mouth and increase the risk of choking.

When gagging happens, take a deep breath and let baby push food forward on their own. If baby is having difficulty gagging food, kneel next to them so they look down at you (this lets gravity do its work) and offer gentle, calming words. See our article, How to Help Baby Gagging on Solids for more tips.

Watch Reza, 7 months old, work through a gag with support from Kary Rappaport, Pediatric Feeding/Swallowing Specialist.

Baby gagging on food is normal.

A baby’s gag reflex is sensitive, and easily activated by toys, their hands, and food. When a baby with no chewing skills puts a piece of food in the mouth, and that food moves in unexpected ways, gagging helps baby safely push food out of the mouth. This is part of learning how to eat. When something new is introduced in the mouth, the brain works to figure out what it is and how to move it around the inside of the mouth. When mistakes happen, the gag reflex is there for protection.

Gagging is not a sign that baby is not ready for solid food, or a signal that you should stop offering solid food. Gagging helps baby push the food away from the throat and lets them try again. Every time a baby gags, they are building skills to safely eat real food. For more information, see our article, How Babies Learn to Chew.

Cooper, 6 months old, gags on applesauce.

Ronan, 7 months old, gags on a blueberry, spits up some, and keeps on eating.

Quentin, 8 months old, gags and coughs on bread with avocado.

Gagging helps prevent choking.

If food is in baby’s mouth and they don’t have good control of it, or food makes its way towards the back of the throat without being chewed, the gag reflex kicks in. When this happens, the throat contracts to help push food forward, and stops the body from swallowing. Baby naturally opens the mouth when gagging, many times, leading to the food coming out of the mouth. While this is happening, the breathing tube quickly closes as extra protection. Gagging is a natural response that is designed to keep food (and objects that baby picks up and puts in the mouth) from entering the breathing tube.

Hillis, 6 months, gags on a vegetable purée.

Addie, 9 months, gags and coughs on asparagus and successfully moves it forward out of her mouth.

Ysabella, 8 months, gags on purple dragon fruit.

Some food textures lead to less gagging.

If you would like to help baby build chewing skills while minimizing gagging, offer food teethers or fibrous foods like a large broccoli floret. These foods tend to cause less gagging because they don't scatter in the mouth. Instead, they hold their shape while firmly touching the tongue and insides of the mouth. This touch communicates information to the brain that helps baby learn. Babies who start with finger foods tend to gag more in the beginning and less later on as they learn how to move the food around in the mouth.

The gag reflex is easily activated by foods that scatter in the mouth, such as rice or grains, and mushy foods like ripe avocado and soft banana. These foods are challenging for baby’s immature chewing skills to manage in the mouth. For example, they cling to the tongue or roof of the mouth, causing intense gagging as baby is still learning how to use the tongue to unstick the food. While this experience is helpful for learning how to manage these textures, it can be hard to observe. Some families choose to puree these foods to minimize gagging; however, babies who are spoon-fed purees tend to gag more later on when they start exploring finger foods.

See our article, How to Help Baby Gagging on Solids, for more information.

Elisabeth and Alison, 6 months of age, gag on very soft banana.

Let baby practice feeding themselves.

One of the most important ways to decrease the risk of choking is to let a baby feed themselves. This way, baby sees, smells, and touches food as they bring it toward the mouth. These senses signal to the brain to prepare the body to bite, chew, and move the food around in a controlled way to swallow.

When food is placed in the mouth by another person, the tongue is not ready to coordinate the movements needed to safely move the food around. Tricking a baby to open their mouth or forcing food in their mouth increases risk in the same way. The research is clear that placing food in a baby’s mouth increases the risk of choking.

See our article, What Is Baby-Led Weaning?, for more information about the safety benefits of self-feeding.

Mahalia, 10 months, gags on some orange stuck to her tongue. If you look closely, you can see the orange isn't actually all that far back in her mouth, but more on the middle of her tongue. She recovers nicely and carries on eating.

While a serious choking incident is rare, it can happen.

Take these steps to help prevent baby choking:

Only introduce solid foods when you see all signs baby is ready.

Create a safe eating environment when offering solid foods to baby.

Make sure baby is seated, properly positioned, and supervised when eating.

Learn how babies learn to chew real food.

Let baby feed themselves and never place food in baby’s mouth.

Offer safe food shapes and sizes for baby’s developmental ability.

Regularly offer foods to build chewing skills so baby can practice.

Regularly check the floor (and other surfaces where baby spends time) and remove small objects that baby can grab and put in the mouth.

Get trained in choking first aid in the unlikely event of an emergency.

Be prepared in case of an emergency.

One of the most important things you can do to protect your baby is get trained in rescue procedures. Some resources:

Our Infant Rescue Guide and Toddler Rescue Guide include visual pictures and step-by-step instructions on how to perform choking rescue maneuvers.

When to seek help

Speak with your pediatrician and ask for a referral to a feeding and swallowing specialist if:

Baby continues to gag at most meals after 2 to 3 weeks of purees.

Baby continues to gag at most meals after 1 to 2 months of finger foods.

Baby is consistently upset after gagging (regular crying, tantrums, vomiting).

Baby is vomiting at most meals, even on an empty stomach.

This article is for informational purposes only, and it is not a substitute for professional advice from or consultation with a pediatric healthcare professional. This information has been created with typically developing infants and children in mind. If your child has underlying medical or developmental differences, discuss your child's feeding plan with their primary medical provider. Please review our Terms and Conditions of Use.

Written By

K. Grenawitzke, OTD, OTR/L, SCFES, IBCLC, CNT, Pediatric Feeding/Swallowing Specialist

J. Longbottom, MS, CCC-SLP, CLC, Pediatric Feeding/Swallowing Specialist

K. Rappaport, OTR/L, MS, SCFES, IBCLC, Pediatric Feeding/Swallowing Specialist

R. Ruiz, MD, FAAP, CLC. Pediatric Gastroenterologist

M. Suarez, MS, OTR/L, SWC, CLEC, Pediatric Feeding/Swallowing Specialist

Ready to get started?

Download the app to start your journey.

Expert Tips Delivered to Your Inbox

Sign up for weekly tips, recipes and more!

Copyright © 2026 • Solid Starts Inc