Access our First Foods® Database in the Solid Starts App.

Learn moreScallops

Shellfish

Age Suggestion

6 months

Iron-Rich

No

Common Allergen

No

Warning

Cook scallops thoroughly before serving to babies. Scallops carry an elevated risk of foodborne illness, and babies are more at risk for severe symptoms.

When can babies have scallops?

Scallops may be introduced as soon as baby is ready to start solids, which is generally around 6 months of age.

A relative of clams, mussels, and oysters, scallops are free-swimming bivalves that live in coastal and deep-sea ocean regions around the world. There are more than 400 species—each with its own features and special taste. In the United States, bay scallops and sea scallops are the most common species available from fishmongers, grocery stores, and online retailers.

How do you serve scallops to babies?

Every baby develops on their own timeline, and the suggestions on how to cut or prepare particular foods are generalizations for a broad audience.

6 months old +:

Serve thoroughly cooked or canned scallops that have been finely chopped and mixed into a soft, scoopable food, such as mashed vegetables or sour cream.

9 months old +:

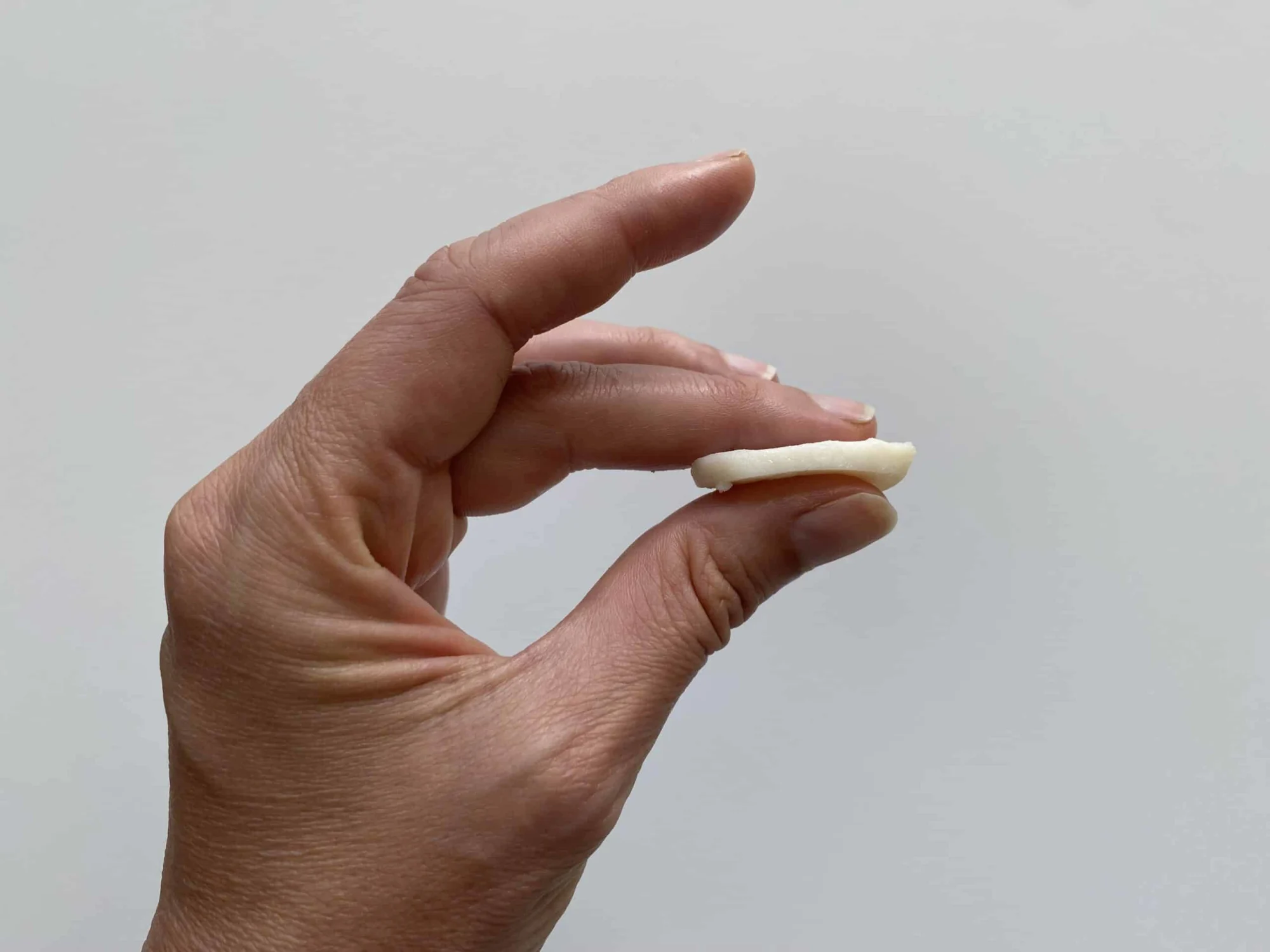

Finely chop or thinly slice scallops that have been thoroughly cooked. Serve the scallops on their own or, if baby struggles to pick up the slippery pieces, mix them into other foods like pasta, rice, or stew.

18 months old +:

Serve bite-sized pieces of cooked scallops or continue with thin slices of cooked scallop and encourage the toddler to spear them with a fork or to pick them up with trainer chopsticks. Model thorough chewing of your own scallop pieces to discourage the child from attempting to swallow bite-sized pieces whole. Refrain from serving whole scallops that are small, such as bay scallops.

24 months old +:

At this age, many toddlers are ready to try a whole large sea scallop. For small scallop varieties, such as bay scallops, continue to slice in half so they are no longer round until you are confident in the child’s ability, which may be closer to 4 years old.

Only offer whole sea scallops when you are confident in the child’s ability to chew what is in their mouth, spit out food that isn't well chewed, and eat other challenging foods. Start with a large sea scallop so that you can coach how to take small bites. Demonstrate how to take a small bite of the scallop with your front teeth. Then, offer a second whole sea scallop to the child and let them follow your lead. Likely, they will bite it in half as you did, though if the child shoves the whole thing in their mouth, refrain from gasping or yelling. Remain calm and say, “That’s a very big bite. You need to chew it.” Then wait patiently as they chew and swallow or spit out the too-big bite.

If you would like to share bay scallops and other smaller varieties with toddlers, cut the scallops in half or thinly slice so that they are no longer round. Smaller scallops present more of a choking risk than large scallops because they are closer in size to the toddler’s airway.

Videos

Are scallops a choking hazard for babies?

Yes. Scallops are firm, slippery, and sometimes small, qualities that increase the risk of choking. To reduce the risk, prepare and serve scallops in an age-appropriate way. As always, make sure you create a safe eating environment and stay within an arm’s reach of baby during meals.

Learn the signs of choking and gagging and more about choking first aid in our free guides, Infant Rescue and Toddler Rescue.

Are scallops a common allergen?

No. Although part of the larger shellfish family, mollusks (like scallops) are not classified as a Global Priority Allergen by the World Health Organization, which only considers crustacean shellfish to be a priority allergen. However, a number of regulatory agencies around the world group the two types of shellfish together and label mollusks as common food allergens alongside crustaceans. Interestingly, shellfish allergies commonly develop in adulthood rather than in children. For those who develop the allergy in childhood, most will not outgrow it.

Individuals with a scallop allergy are more likely to experience reactions to other shellfish in the mollusk family (clam, mussels, octopus, oyster, snail, squid) and also have a >70% risk of reacting to shellfish in the crustacean family (crawfish, crab, lobster, shrimp). If you suspect your baby may be allergic to shellfish, consult an allergist before introducing scallops.

As they are not closely related, being allergic to shellfish does not mean that an individual will also have a finned fish allergy. However, you may need to be careful about the risk of shellfish proteins cross-contaminating finned fish and other seafood, as they are often prepared in the same facilities using shared tools and cooking materials.

As you would do with any new food, introduce scallops by serving a small quantity at first and watching closely for signs of any adverse reaction. If all goes well, gradually increase the quantity over future meals.

Are scallops healthy for babies?

Yes. Scallops are rich in protein and offer essential nutrients like choline, vitamins B6 and B12, zinc, and iodine. Depending on where they come from, scallops can contain varying levels of cadmium, a heavy metal that can negatively affect neurological development when consumed in excess. No food is perfect, so if the family regularly enjoys scallops, aim to offer them as one part of a variety of foods in the diet.

Scallops, like most seafood, carry an increased risk of foodborne illness from a variety of bacteria, including vibriosis. When cooking scallops, take great care to ensure they are fresh and of good quality and make sure to cook them thoroughly.

When can babies have canned scallops?

As long as the scallops are finely chopped to reduce choking risk, babies can have canned scallops as soon as they are ready for solids, generally around 6 months of age. If you would like to reduce sodium in baby’s food, you can choose a low-sodium or no-salt-added brand, when available. Learn more about sodium and babies on our Sodium FAQ page.

When can babies have raw scallops?

There is no age at which eating raw scallops is without risk, so whether or when to serve raw scallops is a personal decision for which you must calculate risk. Raw scallops pose a very high risk of foodborne illness, especially Vibrio, a harmful bacteria that causes watery diarrhea among other symptoms in babies, children, and adults alike. The risk of severe illness is even higher in individuals with complex medical backgrounds, taking stomach acid reducing medications, and/or who are immunocompromised. Cooking shellfish to an internal temperature of 145 F (63 C) helps to kill bacteria in the food.

Can babies have scallop ceviche?

The seafood in ceviche is still raw and uncooked and thus embodies the same risks as any other raw seafood dish. While lime and other citrus juices do have antimicrobial properties that reduce the risk of bacterial pathogens, they cannot fully eliminate them. Therefore, when or whether to serve scallop ceviche should involve the same decision-making process you would use for any other raw scallop dish, knowing that raw shellfish poses a very high risk of foodborne illness.

Our Team

Written by

Expert Tips Delivered to Your Inbox

Sign up for weekly tips, recipes and more!

Copyright © 2026 • Solid Starts Inc